1. The history of opium-eating

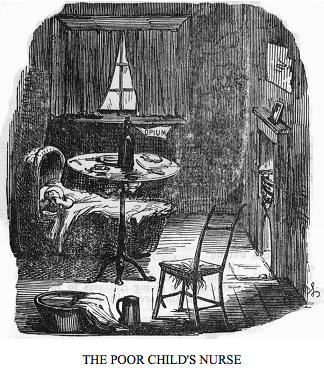

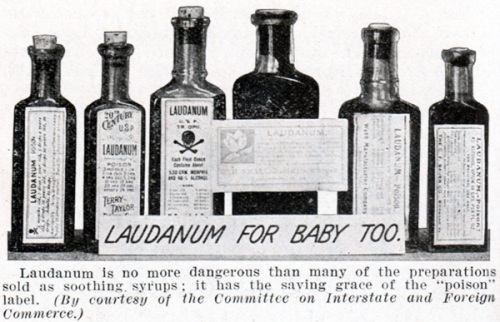

The commencement of the usage of opium for medical purposes can be traced far back to Mesopotamia, Ancient Egypt and Ancient Greece. After years of roaming around the world, it finally arrived from the Middle East to Modern Europe in the 16th century. For the following 300 years, opium and its alcohol derivative laudanum had been prescribed for just about any illness, including asthma, different types of fever, cholera, mumps, rheumatism and physical injuries, such as wounds or fractures. Moreover, it had been commonly given to children to soothe them (Hayter, 2009: 21-25).

However, the awareness regarding the detrimental effects of this herbal analgesic and the addiction it causes, raised only at the end of the 17th century, when the number of opium addicts had already reached staggering heights. Despite these disturbing facts, opium continued to be used broadly in households almost as frequently as aspirin today. Only in the mid 19th century was its reign swayed by the consciousness-raising book Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (Thomas De Quincey, 1821) and was finally shattered in 1868, when the Pharmaceutical Industry declared it poisonous (Foxcroft, 2007: 11). The widely-spread consumption of opium and laudanum is easily explained by the fact that they were effective and inexpensive analgesics, cheaper than beer; therefore even the working-class could afford them (Hayter, 2009: 33).

2. Effects of opium

In general, the consumption of opium is divided into two phases: the early and the late phase. Practically all the beneficent effects, brought on by opium, are associated with the early experimental phase, while the late phase carries pains, as a consequence of the consumer’s attempts to wean off the drug or due to its irregular consumption.

2.1. The early phase: reveries

Reverie is a term referring to daydreaming in a half-awake state of mind and it is related to a period when opiomans experience powerful visions. This “opium dream” cannot be equated with the regular state of being asleep, mostly because opiomans are able to control moderately their dream sequence during a reverie.

It is indispensable to stress that the content of visions and dreams brought on by opium diverges from consumer to consumer, depending on their character, temperament and environment. De Quincey was the first one to bring attention to this fact, asserting that: “If a man whose talk is of oxen should become an opium-eater, the probability is, that (if he is not too dull to dream at all) he will dream about oxen“ (De Quincey, 2004: 7). Opium, therefore, does not convey the power of lively dreaming to those who already haven’t had inspiring dreams, and to those who have had, it can provide improved visions, assembled exclusively of what has already been present in their minds. Concerning the theme of opium’s influence on writers, it can be deduced that: 1) the individual cannot metamorphose into a talented poet and experience fantastic visions as a result of opium-eating, since opium affects solely what is already present in the mind and 2) opium affects individuals distinctly, ergo – among the writers exist individual departures from the conventional effects of opium, which are about to be revealed.

Reverie introduces the feeling of floating and flying, which is related to the feeling of immateriality, ethereality, losing and merging of identity and altered perception of time and space. Considering that these experiences happen in a partially conscious state of mind, they can be controlled to a certain extent and are customarily pleasant in content. In addition, the content of reveries is predominantly passive, non-aggressive and related to the epithets of “lonely” and “distant”. Erotic visions are infrequent, as well as dreams of eating and drinking. During the opium trance, the senses do not render utterly false images to the brain, though imagination magnifies, multiplies, tinges and shapes in a fantastical manner everything a person sees, hears or feels.

Besides the reveries, the initial sensation that occurs under the influence of opium is the decrease of tension and anxiety. In place of doubts, fears, monotony and inhibitions, the opioman gives in to serenity and confidence. The mental activity of the individual is also enhanced: the ability of associating ideas is stimulated and abstract ideas are transformed into images (Hayter, 2009: 41-49).

2.2. The late phase

In the late phase, the power of imagination lessens. The paralysis of critical capability ensues and, as a result, the writer indulging in opium cannot distinguish between their good and bad writings anymore. Opium plays memory tricks in the late phase as well: although the short-term memory is heavily damaged, certain memories (especially childhood memories) can be evoked, with the help of the “uncontrollable activity of the power of association”.

The process of weaning off the drug carries suffering and pains. Some of the most common symptoms are: nausea, cramps, cold sweat, difficulties in breathing, teeth chattering, excessive yawning, sneezing, coughing, shivering or crying and horrendous physical pains. In the late phase, the opioman can neither sleep nor concentrate on anything except on their pains (Hayter, 2009: 54-57).

3. Opium in De Quincey’s book Confessions of an English Opium-Eater

Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821) represents De Quincey’s confession on opium (and laudanum) addiction, where in addition to depicted pleasures and pains brought on by opium, the book also contains his considerations on the subject of opium’s influence on literary creation. In his Confessions, De Quincy confronted the then opium studies, professing that they were:“ Lies! lies! lies!“ (De Quincey, 2004: 41) He claimed that his views on the subject of opium had originated from personal experience, while the ones who wrote exclusively about the terror of opium, possessed no experimental knowledge (De Quincey, 2004: 35). As a consequence, De Quincey’s name became notorious. He was accused of being a pernicious influence, a vile inspiration to the potential addict and there were calls for the work to be suppressed (Foxcroft, 2007: 23] De Quincey briskly reacted to the accusations: „Teach opium-eating! Did I teach wine-drinking? Did I reveal the mystery of sleeping? […] No man is likely to adopt opium or to lay it aside in consequence of anything he may read in a book“ (Hayter, 2009: 49).

3.1. De Quincey’s experience: pleasures and pains of opium

De Quicey insisted that during the first ten years, opium had never had deleterious effects on his psychophysical condition (De Quincey, 2004: 8); on the contrary, he was full of praise for it: „Thou only givest these gifts to man; and thou has the keys of Paradise, oh just, subtle, and mighty opium!“ (De Quincey, 2004: 51) The initial symptoms of opium addiction that De Quincey mentioned amount to the effects of opium adduced in the earlier chapter. Of the utmost importance are the pleasant reveries, that induce the dilatation of time and space. Another characteristic of the opium reverie, according to De Quincey, is “the creative state of eye increased” (De Quincey, 2004: 69]. This syntagma refers to a certain type of visions or mild hallucinations.

However, between 1813 and 1817, De Quincey was increasing gradually his opium dosis and, as a result, soon entered a period of heavy addiction, that was accompanied by tormenting nightmares, as well as by agonizing spiritual, moral and physical pains (Foxcroft, 2007: 28). He dreamt of ugly birds, snakes, crocodiles and human faces stalking him, still experiencing altered perceptions of time and space. Physical consequences of the late phase of opium-eating in the case of De Quincey coincide with the common side-effects: the loss of appetite, insomnia, stomach cramps, etc. (Hayter, 2009: 231).

3.2. De Quincey’s views on the influence of opium on literary creation

The crucial point of De Quincey’s views on correlation between opium and literature has already been mentioned earlier in the text: he believed that opium cannot provide an unimaginative mind with vivid visions, that is to say, opium cannot be the creator of a piece of art; it possesses only the power to intensify ideas or visions already present in the mind of a poet. In addition, De Quincy deemed that childhood memories constitute the foundation of opium-induced dreams and reveries (Hayter, 2009: 235), a theory which is related to the fact that, one the one hand, opium violates short-term memory, but on the other, stimulates long-term memory. According to De Quincey, the creative process of transformation of the past events into poetry, under the influence of opium, functions in three phases: 1) the opiman falls into a reverie, 2) the memories prompted by the reverie pass to a dream and 3) from the dream, the same memories once again reach the conscious mind, from which they are afterwards outpoured into literature.

Moreover, De Quincey believed that outstanding literature could be written during the late phase of opium addiction, but added that these creations would not be complete, mostly because opiomans in the late phase struggle to focus on their writings and finish them (Hayter, 2009: 113-117).

4. Coleridge and opium

Following the example of De Quincey, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, another English writer, began using opium and laudanum as a medicine for his health problems, and after that the well-known course of rising opium addiction ensued. Coleridge attempted to repel the powers of opium and put an end to his habit, but same like De Quincey – failed, and as a result spent the last twenty years of his life living with a doctor who controlled his addiction (Foxcroft, 2007: 33).

Nevertheless, unlike De Quincey, Coleridge cursed opium and his own addiction. His craving for opium, he claimed on several occasions, was provoked “by terror and cowardice of pain and sudden death, not by temptation of pleasure, or expectation or desire of exciting pleasurable sensations” (Hayter, 2009: 31).

Coleridge was convinced for a long time that opium hadn’t influenced his dreams, and admitted only in 1814 that the poem The Pains of Sleep, written in 1803, represented “the exact and most faithful portraiture of the state of my mind under influence of opium” (Hayter, 199). This poem, without a shadow of a doubt, illustrates the horrors of opium dream during the advanced phase of addiction or during the period of weaning off the drug: “The third night, when my own loud scream/ Had waked me from my fiendish dream,/ O’ercome with sufferings strange and wild,/ I wept as I had been a child” (Coleridge, 2003: 283).

A few of Coleridge’s poems are supposedly the product of his opium addiction, among them his major work The Ancient Mariner and Christabel. However, because of the disagreement among the researches regarding the problem of the manifestation of opium in these specific poems, I will engage in the analysis of the presence of opium solely in Kubla Khan, simply because it is firmly believed by many authors that opium must have played some part in the genesis of this poem.

4.1. Opium in Kubla Khan

Kubla Khan initiated numerous polemics concerning the response to the question: did opium, and to what degree, participate in the composing of the poem? It’s difficult to offer a final answer, if we bear in mind Coleridge’s words: “I have in this one dirty business of Laudanum a hundred times deceived, tricked, nay actively and consciously lied” (Hayter, 2009: 195). Now, this statement raises another controversy: did Coleridge, and to what extent, exaggerate or lie in his preface to the poem?

In the preface from 1816, the poet asserted that, shortly before he fell asleep, he had been reading Purchas’s Pilgrimage, a book that tells a story of Kubla Khan who decreed a palace to be built. The poem originated precisely in this deep, three-hour-long sleep, during which the poetic images appeared before the poet as things, followed by a parallel creation of an adequate poetic expression. After he had woken up, the poet began to write down the verses he could recall, but was suddenly interrupted by another affair. When he returned to his desk and attempted to continue his work, the inspiration was gone: now, he could only vaguely remember some general features of the dream.

M. H. Abrams, E. Schneider and A. Hayter, distinguished researches on the subject of opium and Romanticism, clash with one another in clarifying the problem of opium influence on Kubla Khan. Schneider excludes opium as a possible imagination-booster for this poem, contrary to Abrams. Hayter, on the other hand, asserts that the poem is most likely only inspired by Purchas’s Pilgrimage and believes that Coleridge didn’t have a dream experience, but rather deduced his inspiration from a reverie. She derives arguments for her statement from Coleridge’s text published together with Kubla Khan, before 1816, where the poet wrote that the poem was “[…] composed in a sort of reverie brought on by two grains of opium” (Hayter, 2009: 215). Moreover, Hayter stresses that only a rough sketch of the poem (not the whole verses) could originate in such a reverie, because firstly – Coleridge seldom dreamt of landscapes (depicted in the poem) and secondly – the patterns of images and sounds in this poem are too polished to be regarded as a product of a dream or of a reverie (Hayter, 2009: 223).

Abrams considers that Kubla Khan could have been influenced by opium visions in two aspects: 1) in dilatation and interweaving of spaces (the river emerges as a mighty fountain, then transforms itself into a meandering stream and afterwards dilates itself into a vast primordial river that descends into a cave) and 2) in equating the last two verses “For he on honey-dew hath fed/ And drunk the milk of Paradise” (Coleridge, 2003: 146-147) with opium-eating and laudanum-drinking (Abrams, 1971: 46-47).

5. Conclusion

It is now ascertained that some writers were engaged in opium-eating during the 18th and the 19th century; nonetheless, many debates regarding the importance of opium for their literature have arisen. The process of determining if the opium visions had penetrated their writings is hindered by the fact that opium was a writing theme for many writers that weren’t addicted to it: such is the case of Edgar Allan Poe, who was never proved to have been an opium beneficiary (Hayter, 2009: 132). Therefore, it is impossible to certify if the opium references in someone’s writings stem from their personal experience or from the fashion of the era. The biographical facts about writers have already been depleted, hence the experts oftentimes look for corroboration of their statements in the lines of a poem. These untrustworthy pieces of evidence can easily be refuted with a different interpretation of a certain verse, thus the theme of the influence of opium on Romantic imagination remains open for discussion.

Bibliography:

1. Abrams, Meyer Howard. The Milk of Paradise. New York: Octagon Books, 1971. PDF

2. Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. “Kubla Khan.” Lyrical Ballads and Other Poems. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Limited, 2003.

3. Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. “The Pains of Sleep.” Lyrical Ballads and Other Poems. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Limited, 2003. pp. 283-83.

4. De Quincey, Thomas. Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. The Pennsylvania State University, 2004. PDF

5. Foxcroft, Louise. The Making of Addiction: The Use and Abuse of Opium in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Hampshire: Ashgate, 2007. PDF

6. Hayter, Alethea. Opium and the Romantic Imagination. London: Faber and Faber, 2009.

Dedicated to Brana Miladinov, an inspirational teacher who introduced me to English Romanticism.